Forget the intro posts.

We’re diving in.

I’ve wanted to check out the latest features of a Python release without it being in the middle of an explorative search to optimize your work code or make it more readable for a long time now. And I thought this initial post was as good a place as any to fulfil that long-time desire. So today I’ll be looking into what’s new in Python 3.10. I don’t know what the future posts will hold. We'll see.

Step 1: How to get Python 3.10 on your local system?

Heh. This is not intended to be a typical Medium manual post. We’re going to have some fun here first.

So, let’s look at the timeline of version 3.10 so far.

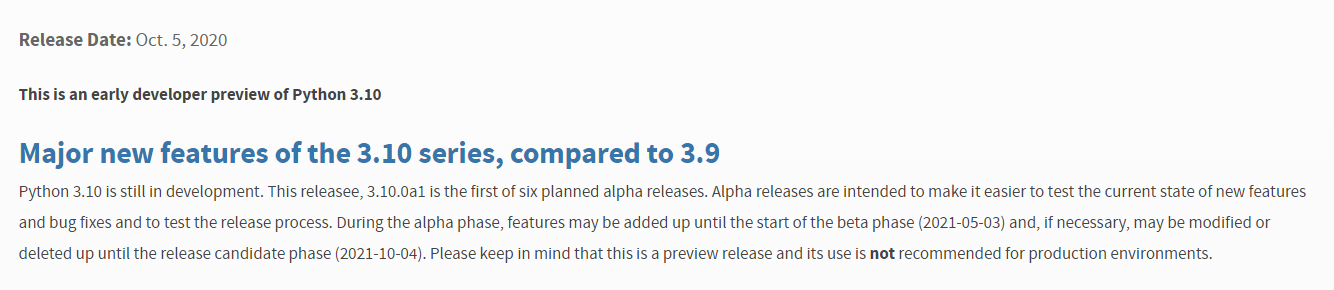

The very first 3.10 alpha was released on Oct 5 2020, a little less than a year ago. And according to the official Python website, there were expected to be only 6 alpha releases - 3.10.0a1 to 3.10.0a6

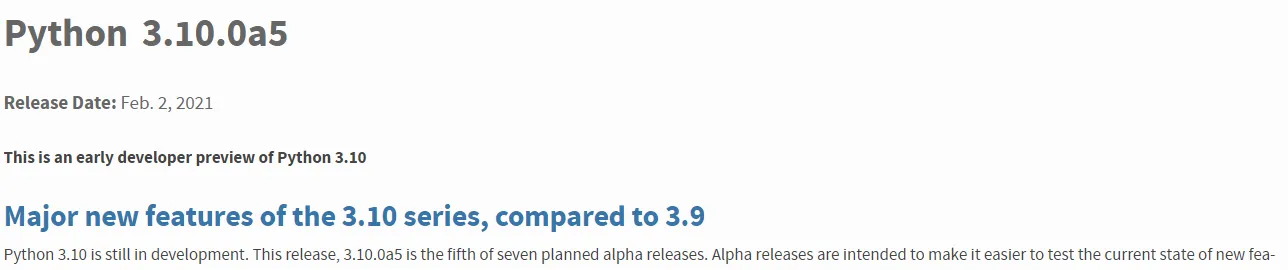

This thought process seems to have continued till 3.10.a4 - Jan 2021.

So the final alpha version was released on Apr 5 2021.

The beta versions - 4 in number - were released like clockwork between May 3 2021 and July 10 2021.

The first release candidate was out on Aug 2 2021. I’ve missed all of these buses so far.

And finally, here we are with the last release candidate for Python 3.10 - Python 3.10.0rc2 - before the final release on Oct 4.

Now, I could have waited for the Oct 4 version (later today), but I’ll check that out when it does. For now, and for the purposes of this post, I’ve downloaded the source code for 3.10.0rc2 from the link above. I could have downloaded the Winstaller-64 bit but I’m using my Ubuntu WSL for the tests here and decided to go the source code route.

Are we there yet?

Step 0 is extracting the tar into a separate location, and the process to build the tar is a simple 3-step process. But if you don’t want to read it from this post, you can also look it up on the README.rst file [rst stands for reStructuredText and is typically used in Python documentation].

The 3 steps are :

- make

- make test

- sudo make install

Each of these steps can take a significant amount of time, the net time required to build ending up being ~50 minutes.

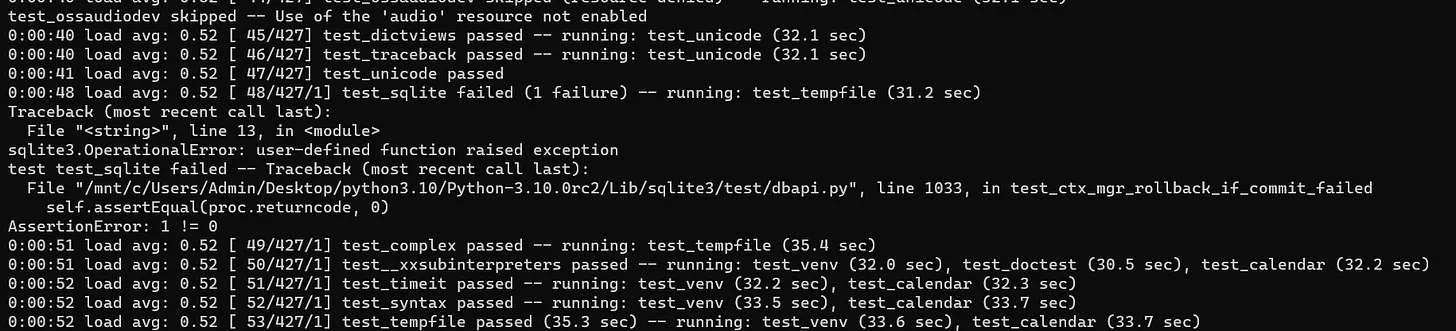

While steps 1 and 3 are expected to install without incident, step 2 might throw a few errors because of some test failures. This might be because there are still parts of the RC that are not handled yet. Then again, I’ve not run tests on the previous versions of Python yet. This might be a common enough occurrence [Requires confirmation].

Example -

If Steps 1 and 3 have completed successfully, congratulations, you’ve just installed python3.10 on your local WSL system and are now ready to try it out. I was ready to try it out.

What’s New?

By now, you’ve probably seen a hundred blogposts and videos cover what’s the latest in Python 3.10 per the documentation, given that the changes haven’t undergone any major changes for the last few alphas and the previous betas. But that wasn’t going to stop me from trying them out and elucidating them myself. It shouldn’t stop you either.

Major changes -

- PEP 634, 635, 636 : Structural Pattern Matching

- PEP 604

- Better error messages

- bpo-12782 (Technically not a change in Py3.10)

I’ll talk about the first three in this post!

PEP 634, 635, 636 : Structural Pattern Matching:

If you’ve used switch..case in languages like C++ and Java, at first blush, this feature should feel like a welcome addition to Python (finally) as opposed to the multiple if..else blocks we’ve had to write all these years. But while the PEPs acknowledge that this is what it looks like, they go on to say this is “but much more powerful.”.

For a simple example consider this code snippet to accept a file name and based on its extension convert the file into a dataframe if supported else return a suitable error message. This is how it would have been written, the only way to write it using <=Python 3.9 -

def pattern_matching_if_else(file_name):

x = file_name.split(".")[-1]

df = None

print(f"File format = {x}")

if x == "json":

df = pd.read_json(file_name)

result = "Success"

elif x == "csv":

df = pd.read_csv(file_name)

result = "Success"

elif x == "pq" or x == "parquet":

result = "Fail"

print("Conversion for parquet Unsupported.")

else:

result = "Fail"

print("Unrecognized file format.")

return (result,df)

Now, Because we have an alternative method to write it, we can nitpick and say it looks not-as-clean-as-it-could-be, the explicit comparison of “x” with the file type causes it be potentially unreadable as the number of cases increase etc. But it’s worked for us all these years. Then again, we don’t have to live like this anymore. Here’s how you Could write it using Python 3.10

def pattern_matching(file_name):

x = file_name.split(".")[-1]

df = None

print(f"File format = {x}")

match x:

case "json":

("JSON File")

df = pd.read_json(file_name)

result = "Success"

case "csv":

df = pd.read_csv(file_name)

result = "Success"

case "pq" | "parquet":

result = "Fail"

print("Conversion for parquet Unsupported.")

case _:

result = "Fail"

print("Unrecognized file format.")

return (result,df)

Let’s unpack this a little.

First of all, it does look a little cleaner because of the lack of repetition. The behavior is the same -

- match the value of “x” against the cases that follow

- For the case where the condition is satisfied, the corresponding codeblock is executed.

- If no case is satisfied, the default case matched by _ is executed.

| Secondly, we can use Or conditions using the “ | ” symbol. |

Thirdly, if you use dataclasses, you can compare custom cases pertinent to your inputs. The example in the official documentation demonstrates the matching of a Point on the X, Y cartesian plane.

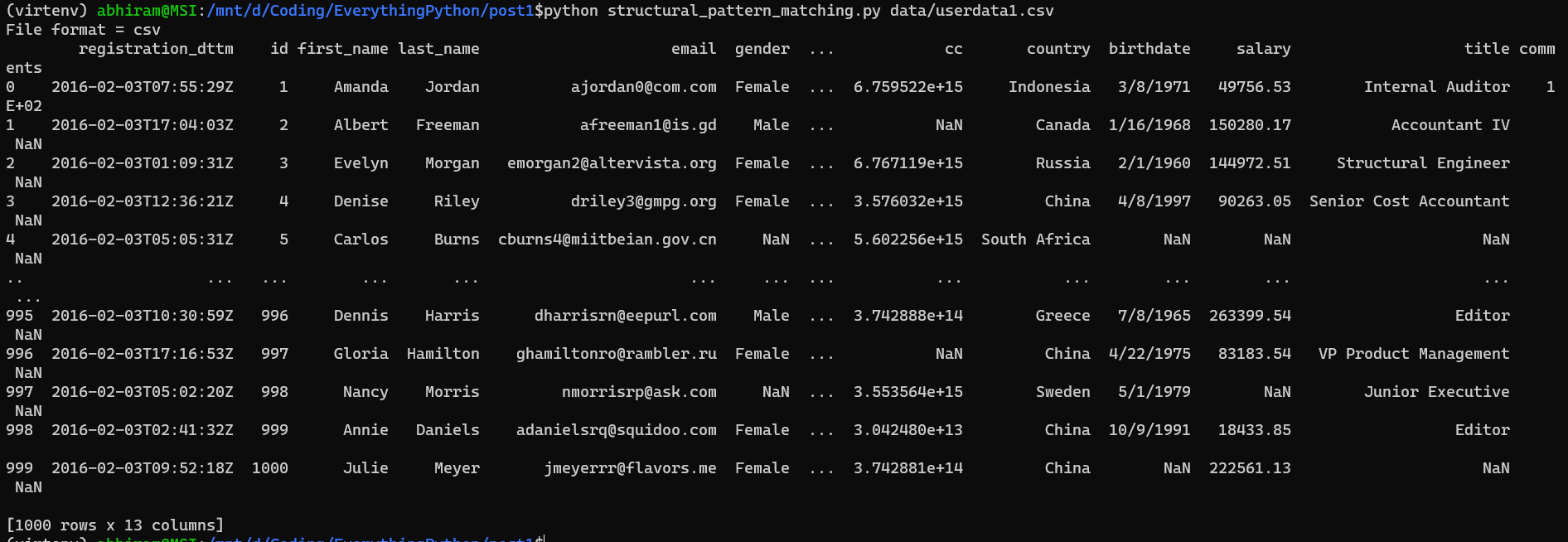

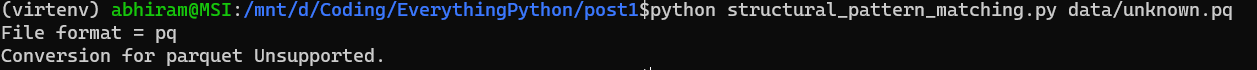

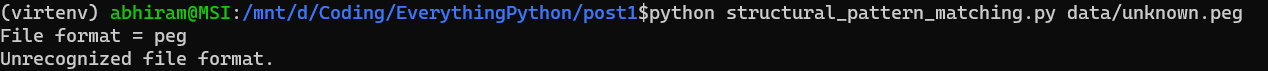

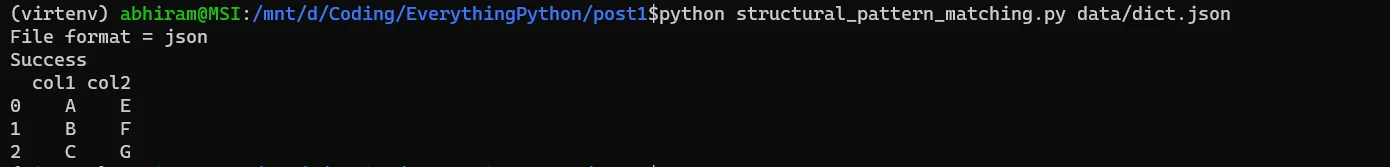

Executing the above code snippet (full in Github repo), this is how it looks -

Can multiple cases be satisfied?

While it logically seems like it shouldn’t be, I tried it out with this naive example anyway. Plugging in these cases in the snippet above -

case "json" if "js" in x:

df = pd.read_json(file_name)

result = "Success"

print(result)

case "json" if "jso" in x:

df = pd.read_json(file_name)

result = "Success2"

print(result)

It looks like if the argument to the code was a file with a “json” extension, it would have satisfied both conditions (the accompanying if conditions are superfluous and are added simply to illustrate the validity of the conditions to a match-ing statement).

But the result was simply “Success” and the second case wasn’t even stepped into.

If you’d like to read more, the advised order of reading is PEP-636, followed by the other two.

PEP 604 : Allow writing union types as X | Y

This is one of those features that you probably don’t care about if you haven’t used it in the past, simply because you just didn’t know it existed.

What are Union Types and when can they be used?

- For now, suffice it to say that it can be used to specify the presence of an argument or return value that can be one of many possible types [Will write a background post about type hints soon].

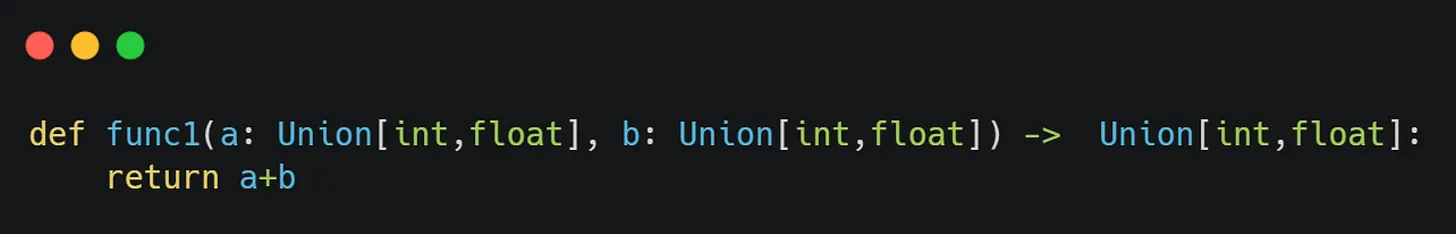

For example -

Here func1 is expected to accept two parameters of type ‘int’ or ‘float’ each and return either an ‘int’ or ‘float’ value.

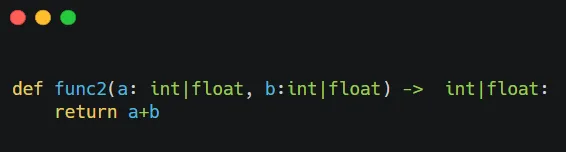

| With Python3.10’s latest feature, you can replace the typing.Union type with the pipe (“ | ”) symbol, effectively making the previous snippet as follows - |

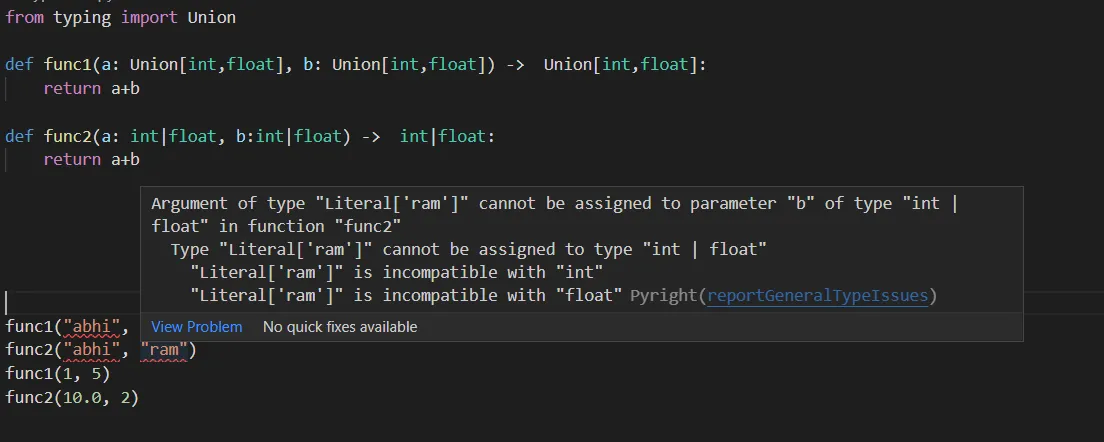

Here’s a code snippet with both usages on Python 3.10 (i.e. typing.Union Is still supported) and also highlighting the expectations of a typechecker like Pyright when used with typehints in place -

The error highlight suggests exactly what is expected out of a typechecker. The point to note is that this checking will not be enforced by the Python interpreter directly. It will have to be by way of typecheckers like these (this is well known to veteran users of typehints since 3.5, but beginners might be flummoxed to not get any errors despite “flouting the rules”).

Better error messages

While this isn’t being touted as a PEP (am I wrong?), this is one of those improvements that’s probably going to help newbies and regular users of Python tremendously alike.

Error messages are what help us understand where our code needs fixing to function. And this is why try..catch blocks and proper Exception handling in coding is heavily encouraged, albeit lazily followed. That said, it would be helpful if Python was a little friendlier in its error messages and told programmers what they’re doing wrong.

To be fair, in all its previous versions, it has Tried.

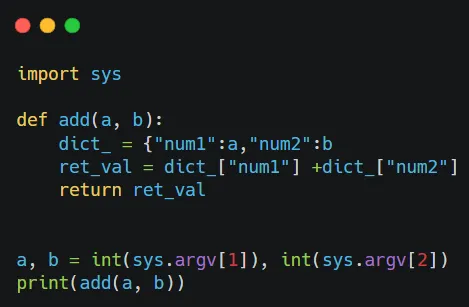

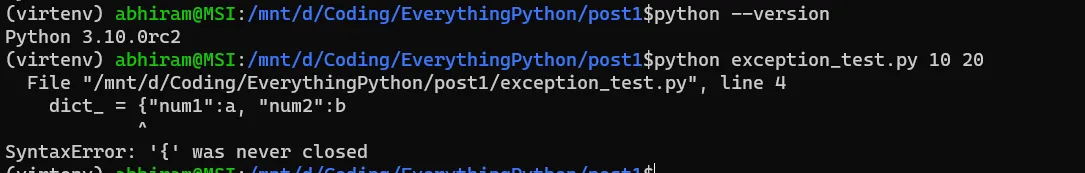

Consider this circuitous way of adding two numbers with a dictionary in the middle with no real purpose -

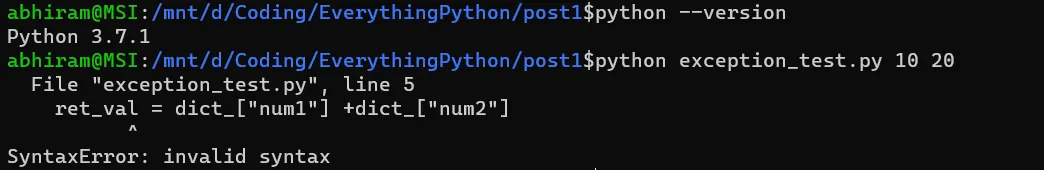

In Python 3.7 and up until Python 3.9, this is what you’d get if you tried executing this buggy code snippet.

The problem is indicated to be at a line succeeding the real offender, the incomplete dictionary syntax.

This has gotten better with Python 3.10 -

letting us know the Exact error for failure.

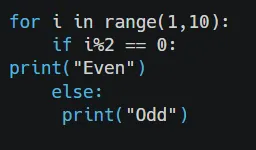

Then there’s the dreaded beginner-challenge : Indentation Errors!

I’ve seen so many people starting with Python coming in from a braces-based language tripping on this with code snippets (exaggerated) like so -

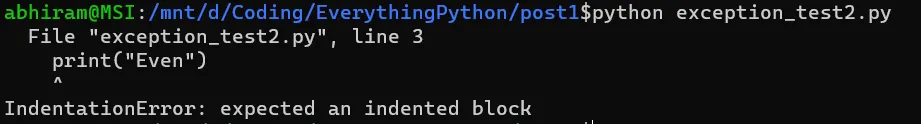

Only to be greeted rudely on versions <=3.9 with -

Well…Maybe , this particular example’s error isn’t so much rude, as curt.

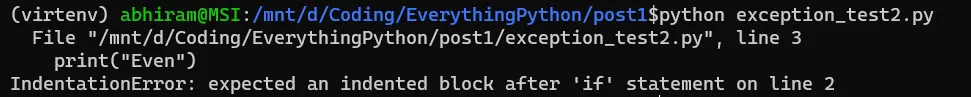

But the equivalent Python 3.10 error Is warmer!

Now it is worth noting that the way this error message reads is mildly strange. It says “…after ‘if’ statement on line 2” and it is to be read as such - i.e. the if statement was on line 2 and the error is after that - on line 3 as hinted in the first line of the error. I wouldn’t be surprised if oversight made people look For the indentation error on line 2.

There are a lot more of these friendlier, more exact exception messages based on situation -

- Missing commas in collection literals and between expressions

- Unparenthesised tuples in comprehensions targets

- try blocks without except or finally blocks

- Usage of “=” instead of “==”

I’ll add code snippets of my own for all of these eventually, but I encourage you to check them out in their current form here - https://docs.python.org/3.10/whatsnew/3.10.html#better-error-messages

I’m really looking forward to today’s release party of 3.10 official for three reasons.

- I’ve had a chance to try out most of the new features and I Love the amount of attention this language continues to get after decades of first being introduced.

- This is the first time I’ve gotten wind of the launch of a release prior to its happening

- It’s finally given me a reason to break out of my head and start my own proper Python based blog. Something I’ve wanted to do for Years now. Hopefully I’ll be able to keep this up.

Catch it here - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHT2l3hcIJg

Until next time!

PS - The code accompanying this post can be found at - https://github.com/everythingpython/post1

PPS - My thanks to Randy Au for posting great posts on his blog consistently - Counting and being the inspiration for getting off my behind and finally being able to do this. Check his blog out as well :)